This essay is the third of a series of analyzing graphic memoirs from my first year english course: The Craft of Writing with Professor Diedrick.

Hereditary

In the United States, we live in a political climate where the plight of immigrants are shadowed by the cries of xenophobia. Daily, we hear rhetoric that antagonizes immigrants and new restrictions on who can come across the borders. The refugee experience often gets oversimplified and is grouped into the American Dream trope. Some immigrants may have the choice to leave their home country, but refugees are simply trying to escape theirs. In Thi Bui’s graphic memoir, The Best We Could Do, the reader follows the impacts of the Vietnamese war on her refugee family as they carry their emotional baggage to the United States. Bui’s parents endure several hardships such as the disappearance of relatives, loss of children, and living in a police state. Their unresolved trauma from years of living in constant survival mode as refugees affect their relationship with their children in an attempt to protect them from their history. But, the symptoms of trauma are passed down to Thi and her siblings, resulting in a cycle known as intergenerational trauma. Bui retells parts of her family’s traumatic history in Vietnam in order to break the cycle and improve her relationship with her emotionally distant parents: “‘I might have been happy to just dwell in my trauma, but with a baby in hand, I was really concerned with not passing on that trauma myself, and so I needed to filter stuff out so I could pass on something cleaner’”(Yu).

Thi Bui’s narrative strategy is non-linear. She begins her memoir with the birth of her baby and her mother’s absence from her delivery. Bui gives us insight into why her mother was distant by introducing her siblings through stories of their birth in Vietnam. She does this throughout the entire comic: she switches from her parent’s experience to show how it affected her own childhood experience. Bui explains why her parents are the way they are (emotionally distant) and how that was the best they could do given their trauma. The complex timeline discredits reality in the memoir for some readers. However, in the introduction of Michael A. Chaney’s Graphic Subjects, he describes the differentiation between the “narrator ‘I’” who is the author and the “narrated ‘I’” who is the visual character in the comic. He presents this to argue that this is an example of how autobiographies rely on emotions to build credibility which Bui does as she narrates the childhood of Thi (Chaney 3). Bui also built credibility because her memoir is directly tied to historical contexts such as the Vietnam war.

Thi Bui’s parents, as first generation refugees, experienced terror daily in their adult lives. In Thi’s father Bo’s case, he experienced terror since infantry. Guus van der Veer, a renowned expert in counselling trauma victims and refugees, has broken down the experiences of refugees in order to write his book Counselling and Therapy with Refugees and Victims of Trauma : Psychological Problems of Victims of War, Torture and Repression. His book is meant for those who do social work and it gives psychological insight into what mental health problems may plague the refugee. Veer breaks down traumatization of refugees in three phases: “increasing political repression”, “major traumatic experiences”, and “exile”. The first phase is where the refugee notices changes in their community due to social or political changes. The second phase is where the refugee is directly a victim of a traumatic experience such as detention, violence, torture, the disappearance of relatives, hardships during escape, or guilt. The third phase is where the refugee is now in their host country and they “may experience a lot of stress… [from] physical conditions (climate and landscape) and social and cultural conditions (norms and customs) which are different” (Veer 19) as well as occasional “racial prejudice [and] xenophobia” (Veer 20). Veer also details the consequences of traumatization in a family context as: “dysfunctional circular interaction, disturbances in communication, family secrets, overprotectiveness, parentification, … a hierarchy of suffering, and transgenerational phenomena” (Veer 41). Transgenerational trauma is the passing of trauma from one generation to the next whereas intergenerational trauma is the passing of trauma between two generations (Mohn). The trauma that Ma and Bo go through passes on to their kids through their behaviors as a result of the trauma.

Thi’s parents have gone through these phases of traumatization at different stages in their lives. Bui illustrates her father’s trauma in her fourth chapter: “Blood and Rice”. Bo’s past completely skips the first phase of traumatization as he was already born into instability due to famine and poverty as a result of war. His parents and grandparents were not an example of a happy family, but one desperate for survival. Bo’s mom was the only one who truly cared for him, but his father cheated and threw her out leaving him to be taken care of by his grandfather. The second phase is complete when he lives with his grandfather in his native village. They are terrorized by French soldiers and he witnesses the slaughtering of his village as he hides in fear for his life. He acknowledges his behaviors are a result of this at the end of the chapter: “You know how it was for me. And why later I wouldn’t be… normal” (130). Thi’s mother, Ma, has a comfortable upbringing as her family is a part of the upper class. However, the first phase is complete when she goes to college and becomes aware of political turmoil. The second phase is when she loses her first child and continues to make sacrifices as she lives in fear under a police state. And finally they both fulfill the third phase when they relocate to the U.S; Ma is forced to take a job below her skill level, Bo is unable to adjust to his new environment so he stays home with the kids, and they experience prejudice. In order to protect their kids, Thi’s parents stay

quiet about their past and the sacrifices they made along the way which negatively impacts Thi and her siblings. Ma’s failure to adjust to American society and relationships results in her abuse of prescription pills in order to overdose and “[they] avoided ever talking about that incident… to the point that Ma thought [Thi] didn’t remember it” resulting in family secrets (Bui 28). Another consequence of their trauma is dysfunctional interaction: their inability to express their emotions to their kids. Bui reflects that for her “mother, ‘I love you’ sticks in the throat. So she buys gifts and cooks.”(Bui 38) while her father smoked and terrified them with his anger and supernatural paraphernalia.Veer uses the phrase “transgenerational phenomena” to describe the cycle of intergenerational trauma. He defines the phenomena as “the legacy of a parent … [that]

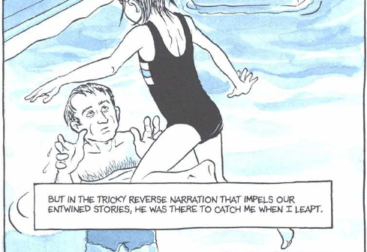

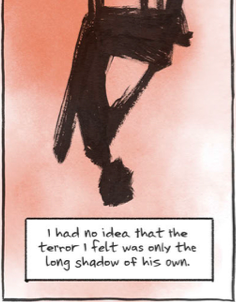

take[s] the form of a certain attitude or feeling towards life, or people in general, as a result of experiences developed during their lifetime, and which is transferred to the child” (Veer 45). Bui alludes to this when she shares that she was taught unintentional lessons that “came from [her parent’s] unexorcised demons… and from the habits they formed over so many years of trying to survive” (Bui 295). She also inherits traits from her parents: “This… is my inheritance: the inexplicable need and extraordinary ability to run when shit hits the fan. My refugee reflex”(Bui 305). Her parents were focused on staying inside and locking the door, something they practiced in Vietnam, but this difference in actions shows Thi’s ability to branch away from her parents mindset. If they had stayed inside, their trauma could have killed them. When Thi becomes pregnant, she realizes she doesn’t want her kid to live in her shadow so she begins to write the memoir to forgive and understand her parents.

Without researching her parent’s past, Thi would never figure out why her parents treated her so poorly. She grew up with so much anger against her parents for being emotionally distant. But her frustration of not being able to care for her elderly parents as well as the birth of her child motivates her to end the cycle of intergenerational trauma. In order to heal her own trauma she has to understand her parents’: she “ uses parallelisms between Thi and her parents to demonstrate how … insidious trauma is felt across two generations”(McWilliams 323). When she gives birth she has to step up and sacrifice, like her parents did for her, and wake up every 90 minutes to try and feed her child. She also uses an image of her father as a scared boy and juxtaposes it with her fear of her own father. Instead of pretending to forget her trauma like her parents have done, she does the work of reopening her and her parents’ wounds. The title alludes to her parent’s ability to care for their kids with their trauma as well as “the second generation [falling] short in caring for their parents” (McWilliams 319). It’s important to note that she was able to recognize what she felt was a shadow of her parents’s trauma. Her parents weren’t able to heal from their trauma which allowed for it to pass on. But, writing this book was her way to heal, yet she recognizes that it’s uncertain if she’ll inflict emotional damage on her son anyway.

Works Cited

Bui, Thi. The Best We Could Do : An Illustrated Memoir. Abrams ComicArts, 2017

McWilliams, Sally. “Precarious Memories and Affective Relationships in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.” Journal of Asian American Studies, vol. 22, no. 3, Oct. 2019, pp. 315–348

Mohn, Elizabeth. “Transgenerational Trauma.” Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2019.

Yu, Mallory. “Cartoonist Thi Bui Weaves Together Personal And Political History.” NPR, NPR, 1 Aug. 2018

Veer, Guus van der. Counselling and Therapy with Refugees and Victims of Trauma : Psychological Problems of Victims of War, Torture and Repression. Vol. 2nd ed, Wiley, 1998