Death by Society

Coming out as queer is not easy–an understatement of the century. When I came out, every day before that was an anxiety riddled internal battle. I knew what possibly awaited me: rejection from my friends, family, and society itself. Ultimately, I realized that my sexual orientation was inseparable from my identity and I would no longer censor an integral part of who I am. I discovered that I’m privileged in many ways to live in a time where several activists have already begun the fight for our rights and liberation since the 1950’s (“Milestones in the American Gay Rights Movement”). In Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, her father Bruce’s sexual repression is a result of living in the beginning of this movement and in a not so accepting small town. His internalized shame manifests as obsession with creating facades: his nuclear family, and home restoration; and emotional, verbal, and physical abuse. She first explicitly compares Bruce to Daedalus, but as her coming of age story spirals he is more like Icarus. Bechdel alludes to the characters from the Greek myth “Icarus and Daedalus” in order to capture the complexity of their relationship over time.

Bechdel introduces the novel explicitly comparing Bruce to Daedalus: “Daedalus of décor … skillful artificer, that mad scientist who built the wings for his son and designed the famous labyrinth”(6). Bruce shares craftsmanship with Daedalus, but Bruce constructs images of a happy nuclear family in order to assimilate into society as a closeted gay man. Bechdel recalls the time they went to church and the community’s impression of him was an ideal father, “He used his skillful artifice not to make things, but to make things appear to be what they are not” (16). He wanted to be perceived as a straight man with a nuclear family; normal. This is also seen in the form of his obsession with the house. His home restoration project is his own labyrinth and in it he traps himself and his internalized shame. Because he is unable to be his true self in his hometown, the built up frustration is the Minotaur in this metaphor. This frustration causes him to physically and emotionally abuse his family, “My mother, my brothers, and I knew our way around well enough, but it was impossible to tell if the minotaur lay beyond the next corner”(21). If the kids messed with any of the details in the house, they were hit. He was destructive towards his family and together they were all trapped in his labyrinth. Bechdel alludes to the house being a labyrinth due to its maze-like details and its function, “In fact, the meticulous, period interiors were expressly designed to conceal [his shame]” (20). His obsession with constant decoration results in the abuse of his own family. Bechdel compares her father’s disregard for his family members when it came to his house to Daedalus, “[he] too was indifferent to the human cost of his projects” (11). Daedalus let his son fall from the sky, but Bechdel reverses this metaphor where now her father falls from the sky.

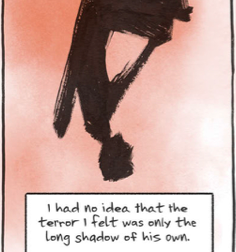

The parallel is hard to ignore, but in the first pages Bechdel immediately foreshadows the reversal of this metaphor, “Considering the fate of Icarus … [i]n our particular reenactment of this mythic relationship, it was not me but my father who was to plummet from the sky”(4). Bruce, like Daedalus, allowed Alison, like Icarus, to fly with his support. But, Bruce becomes Icarus in the way they both recklessly tempt fate and ultimately fall into the water. His obsession with facades and artifice is thrown out the window when Alison discovers a photo her father took of Roy, “It’s a curiously ineffectual attempt at censorship… Why leave the photo in the envelope at all?”, she easily finds the photo in an envelope labeled “family” (101). It’s almost as if he wanted someone to find it. He continues risky activity when he decides to purchase beer for an underaged boy and continues to see other highschool aged boys in his library. As time progressed, he was not as precautious or overly secretive. When Alison comes out as lesbian over mail, she’s only able to see her father once before he dies. Alison and her bond and share an intimate moment where he boldly shares his experiences with men with her and she compares him to a “splendid deer I didn’t want to startle” (221). As a family the Bechdel’s did not express much of their emotions, so when her father spoke she felt that if she said anything he might retract everything he said and he’d go cold again. As she listened to him she also felt as the father figure listening to their child admit to something shameful. In that way she is Daedalus and he is Icarus. Ultimately, the internalized homophobia catches up to Bruce. His obsession with constructing the perfect illusion of a “normal” life pushes him to commit suicide knowing he will never be free in this life; he falls into the ocean.

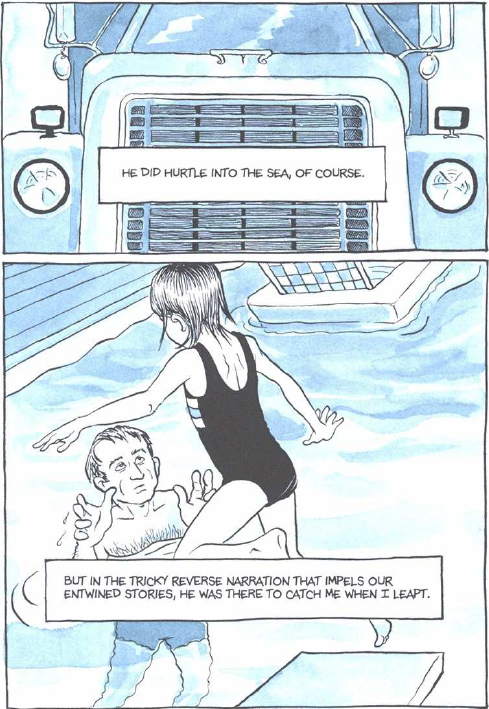

On the final page, Alison is illustrated ready to jump into the pool. Unlike we’re led to believe, her father is there for her. Despite his death, she brings her father back to life in the last panel to show the reader that he had an enormous impact on her life. Bechdel reverses the metaphor yet again: “in the tricky reverse narration that impels our entwined stories, he was there to catch me when I leapt”, implying that she was Icarus and her father Daedulus (232). In this final panel, Bruce was not always emotionally absent and her relationship with Bruce was more complicated than the myth could capture.

The different ways in which Alison and Bruce are or aren’t like Icarus and Daedalus shows how similar they are to each other. Alison compares herself to her father in order to understand herself through her father’s experiences. Bechdel highlights their similarity with photographs, “one is a picture of herself, snapped by a girlfriend; the other is a picture of her father at twenty-two… ‘it’s about as close as translation can get’” (Wolk). Bechdel wanted to understand her father beyond her own experience with him and the faulty images he created.

Works Cited

“Milestones in the American Gay Rights Movement.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/stonewall-milestones-american-gay-rights-mov ement/.

Wolk, Douglas. Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean. Da Capo Press, 2007.

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: a Family Tragicomic. Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

This essay is the second of a series of analyzing graphic memoirs from my first year english course: The Craft of Writing with Professor Diedrick.